The North American Monsoon in Arizona

The North American Monsoon is a well-defined meteorological event that occurs during the summer throughout southwestern North America, including Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and sometimes California, Nevada, and Texas. The primary wind flow into Arizona is from the west, maintaining dry conditions across the state much of the year. Into late June and early July, winds start to come from the south. These southerly winds often transport low-level moisture, triggering summer thunderstorms.

The key to the North American Monsoon is the shift in wind direction each summer, from westerly winds to southerly winds.

The development of the Monsoon Ridge in late June or early July is often the starting point for establishing the monsoonal shift. The Monsoon Ridge is an area of high pressure that ideally builds in the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. The strength and location of the Monsoon Ridge is often the main factor to initiating monsoon season activity.

Things to know: the plural usage monsoons as in "when the monsoons arrive ..." is not the correct way to use the meteorological term. A monsoon is a season; a monsoon is NOT a thunderstorm. The singular usage monsoon should be applied in the same manner that the word "summer" is used because both are seasons. Consequently, the proper usage is monsoon thunderstorms when describing thunderstorm activity during the season.

Monsoon thunderstorms are convective in nature. Convection is caused by warm air rising, so convective thunderstorms are powered by intense surface heating. Significant moisture moving into Arizona is also needed to generate thunderstorms. Initially, low-level moisture streaming into Arizona often comes from the Gulf of California, called gulf surges. Moisture can also move into Arizona from the eastern Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico, or even from the Sierra Madre Occidental forests in Mexico.

A lifting mechanism is another ingredient needed for thunderstorm activity in Arizona. The Mogollon Rim in central Arizona acts as a lifting mechanism, forcing warm, moist air to rise and then condense. Afternoon thunderstorms along the Rim can sometimes move down into the Phoenix area, generating thunderstorms later in the evening.

In 2008, Arizona weather agencies and researchers decided to define the monsoon season as June 15 to September 30. In this way, similar to the Atlantic hurricane season, information for monsoon activity could be aligned across the various states potentially impacted by the monsoon. The "legacy" operational criterion for the onset of monsoon conditions, specifically for Phoenix, was defined as a "prolonged (3 consecutive days or more) period of dew points averaging 55°F or higher." A 55°F dew point in Phoenix is connected to the amount of water in the atmosphere needed to generate a thunderstorm. The definition of dew point is the temperature when condensation will occur, so the higher the dew point, the more water available in the atmosphere for thunderstorms. Additionally, a 55°F dew point in Phoenix (or a 54°F dew point in Tucson) is associated with one inch of precipitable water in the atmosphere. Precipitable water is the amount of water in the atmosphere if the water in an imaginary column above the surface was condensed. To generate a thunderstorm in Phoenix (or Tucson), the atmosphere needs at least one inch of precipitable water.

Generally, temperatures needed to generate convective thunderstorms in Phoenix range from 100° to 108°F, with the ideal temperature, on average, 105°F. Temperatures needed to produce thunderstorms in Tucson can be somewhat cooler because Tucson has a higher elevation than Phoenix. Overall, cloud coverage or cooler temperatures can suppress thunderstorm activity anywhere across the state. Additional thunderstorm activity during the monsoon season can include flash flooding, downbursts, hail, lightning, and strong straight-line winds.

Bursts and Breaks

Thunderstorms don't happen every day during the monsoon season, but instead follow patterns of "bursts" and "breaks".

Burst: a brief period of excessive thunderstorm activity. There is often strong surface heating and strong southerly or southeasterly moisture transport into Arizona during a burst. This setup creates intense atmospheric destabilization and leads to strong widespread thunderstorm outbreaks. A "burst" can also be caused by gulf surges.

Break: a brief period of little to no thunderstorm activity. A break can be caused by movement or expansion of the subtropical ridge of high pressure, which can stabilize the atmosphere and eliminate widespread thunderstorm activity.

Summer Thunderstorms

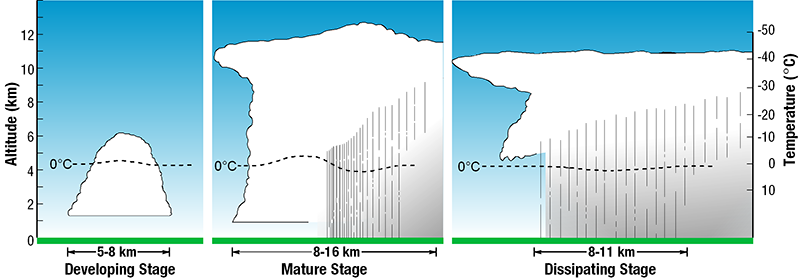

A storm cell is a single cloud that can build into a thunderstorm. There are three basic stages of thunderstorm development: the cumulus (developing) stage, the mature stage and the dissipating stage. Storm cells in Arizona are generally short-lived, and the life cycle of a single thunderstorm cell usually lasts less than an hour. There can be several storm cells in the same location at different life cycle stages, which is called a multicell thunderstorm.

The first stage of thunderstorm development is the cumulus (developing) stage. In this stage, the primary activity is pronounced vertical uplift inside the cloud. Warm, moist air is lifted adiabatically and condenses to form cumulus-type clouds. As the updraft stage continues, the formation of towering cumulus begins. Little or no precipitation occurs during this stage.

The second stage of thunderstorm development is the mature stage. This stage is characterized by both updrafts and downdrafts. Updrafts are caused by warm air rising, while downdrafts are associated with air that is pulled down by precipitation. Normally, downdrafts will be found near the leading edge of the thunderstorm cell. The descending downdrafts from the thunderstorm will often hit the ground and be forced out ahead of the storm, creating a gust front.

In the Arizona desert, these gust fronts can transport significant quantities of dust and sand, creating a large wall of dust moving ahead of the thunderstorm. The term haboob is specific to this type of dust storm formed from the gust front of a thunderstorm.

Heat

In the last 30 years, Arizona’s summer daytime temperatures have increased about 0.4°F per decade. However, summer nighttime temperatures have increased at a greater rate, at about 0.6°F per decade. This nighttime temperature increase is due to the urban heat island (UHI), where buildings store heat during the day and release the heat slowly at night. Consequently, night temperatures are hotter than they used to be, increasing the risk of heat-related illness.

Heat is the number one weather-related disaster in the United States. According to the Maricopa County Department of Public Health, 425 people died in Maricopa County in 2022 due to a heat-related illness. In 2023, that number increased by 52%, where 645 people died. Phoenix endured its hottest summer on record in 2023, with 106 days of 100°F+ temperatures and 55 days of 110°F+ temperatures. On average, Phoenix usually has about 99 days of 100°F+ temperatures and about 21 days of 110°F+ temperatures in the summer.

Some people are more vulnerable to heat than others, which includes infants, younger children, the elderly, and those with chronic health conditions. In order to prepare the public for heat events, the National Weather Service launched a tool called HeatRisk. HeatRisk takes into account 1) how anomalously warm the temperatures are for the time of year, 2) how long the heat is going to last, and 3) if the temperatures can lead to a higher risk of a heat-related illness (based on CDC data).

Heat Safety

- Stay hydrated on a regular basis. Drink water before you feel thirsty.

- Wear light-colored clothing along with a hat, sunglasses, and sunscreen to protect from the sun.

- Stay inside in cool locations between 10am and 5pm (these are the hottest times of day).

- Never leave children or pets inside a locked vehicle. Heat-related deaths can happen in minutes inside a hot vehicle!

Click here for an interactive map of cooling centers across Arizona: Arizona's Cooling and Hydration Network

Lightning

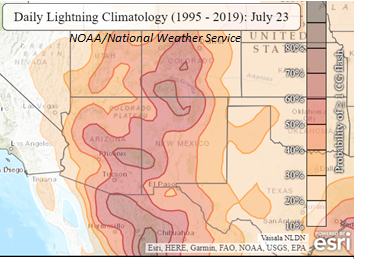

Whenever there is lightning, there is ALWAYS thunder, so using the term thunderstorm means that lightning is or will occur during storms. Lightning can happen any month in Arizona but is much more prevalent during the monsoon season. Arizona is well-known for high-based thunderstorms, which provide an easier view for cloud-to-ground lightning. Cloud-to-ground lightning only makes up about 10% of all lightning strikes. The majority of lightning is cloud-to-cloud or intra-cloud (inside the cloud). Intra-cloud lightning is also called sheet lightning.

Lightning travels at the speed of light; thunder travels at the speed of sound. To estimate how far away the lightning strike happened, start counting after seeing the lightning. Every 5 seconds equals about a mile; for example, counting 15 seconds and then hearing thunder means the lightning strike was 3 miles away.

People have been hurt by lightning from storms as far as 10 miles away, and lightning can travel up to 200 miles from the storm. The last lightning fatality in Arizona was July 20, 2016 when a hiker was struck on Mt. Humphreys. All Arizona lightning fatalities in the last 30 years happened when people were outside, like hiking or camping. The safest place to be during a thunderstorm is inside a building with closed windows.

Dry thunderstorms are especially common before the monsoon season is fully established. If lightning sparks a fire, a "dry" thunderstorm might not drop enough rain to put out the fire.

Flash Floods

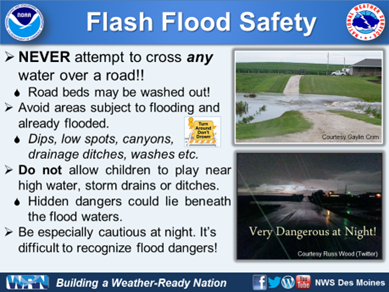

Flash floods are deadly. Arizona has, on average, 4 flooding fatalities every year. Flash flood season in Arizona corresponds to monsoon season, although flash floods can happen any time of the year. A flash flood is caused by an extreme amount of precipitation often from a storm miles upstream. The flood waters typically move very quickly downstream, lasting only a few hours. Cities and deserts are more susceptible to flash flooding due to the impermeable surfaces. Never cross roads with posted barricades warning about flash flooding or any roads covered with water; instead, turn your car around and cross a road without barricades or flood waters.

Wildfire is part of the climate of the Sonoran Desert, however, wildfires can easily grow out of control, burning hotter and more intense. Strong, intense wildfires can destroy vegetation and even burn the soil. Burned vegetation and soil creates an area called a burn scar, which decreases infiltration and contributes to flooding. Consequently, the next rain event over a burn scar area can trigger a significant flash flood or even a dangerous debris flow.

Hail

Hail is generally a summer thunderstorm feature, although hail can happen with any strong thunderstorm. Hail forms from a strong updraft in a tall thunderstorm; the stronger the updraft, often the larger the hailstone. Hail showers in Arizona are generally brief, usually not more than 10 minutes. The largest hailstone measured in Arizona was 4.5 inches in diameter in Mayer, Arizona in 1995. While hailstones in Arizona are generally small (pea size), Phoenix did experience the costliest hail event on record for the United States, causing almost $3 billion in damages October 5, 2010.

Dust Devils

A dust devil is a vortex of dust-filled air created by extreme surface heating. Diameters of a dust devil range from 10 feet to greater than 100 feet; the average height is between 500 to 1000 feet but can extend to several thousand feet tall. Dust devils display some characteristics similar to tornadoes: both cyclonic and anticyclonic dust devils have been observed and large dust devils have been observed with accompanying "suction vortices" (smaller dust devils rotating around the main vortex).

A dust devil is not a tornado. The biggest difference is that dust devils generate from the ground and move up into the atmosphere, while tornadoes initiate from clouds and move down to the surface.

Gustnadoes

Gustnadoes are features that seem to combine some of the characteristics of dust devils and tornadoes. A gustnado is a tornado-like vortex that appears to develop on the ground and extend several hundred feet upward. These vortices generally develop along the leading edge of an outflow boundary from a thunderstorm cell. Although generally of limited duration, the winds of gustnadoes can be strong enough to cause damage. Gustnadoes can sometimes be misidentified as fires because of the appearance of the winds.

Tornadoes

The definition for a tornado is a "violently rotating column of air" that descends from a cloud and touches the ground. Severe tornadoes are fairly rare in Arizona. Although Arizona might often have several of the weather ingredients needed to produce tornadoes (such as abundant moisture, superadiabatic heating, etc.), only rarely do all of these tornadic ingredients happen at the same time. One tornadic ingredient often missing over Arizona in the summer is the subtropical jet stream (a narrow corridor of very strong winds generally found about 6 miles up in the atmosphere).

Still, tornadoes have occurred in Arizona and will occur again in the future; on average, four to six tornadoes spawn in Arizona every year. Arizona tornadoes are often very weak (EF0, EF1) and last only for a few minutes. Arizona also experiences funnel clouds generated along severe thunderstorms, although more often from thunderstorms along cold fronts in the fall or winter. A funnel cloud is a vortex of spinning air generated from a cloud but not reaching the ground. Funnel clouds generated from a cold front are often called cold air funnels. If a funnel cloud extends to the ground, it becomes a tornado. A funnel cloud should not be taken lightly as any funnel cloud has the potential to become a tornado.

Tornado Safety

- DO NOT ATTEMPT TO OUTRUN A TORNADO. Tornadoes may not move at all or might move incredibly fast (50 mph or more, sometimes possible during Arizona's fall and winter storms).

- If caught out in the open, go to the lowest location (like a ditch, culvert, or arroyo) and drop flat to the ground. Cover your head. Watch for flash flooding.

- If caught in your vehicle, ABANDON your vehicle and find the lowest location (ditch, culvert or arroyo). Cover your head. Watch for flash flooding.

- If in a building, go to the smallest room on the lowest floor. Put as many walls between you and the storm as possible. A bathroom is generally considered a good safety area given the number of pipes in the walls. Cover your head with a helmet or mattress.

Straight-Line Winds

Although tornadoes are rare in Arizona, strong winds resulting from downbursts are quite common during the summer thunderstorm season. Straight-line winds are often generated by downdrafts. When the downburst hits the ground, strong winds will move out in all directions in straight lines (there is no rotation in straight-line winds). While not tornadic, straight-line winds can cause significant damage.

A downburst can be categorized based on the overall size of the feature. A microburst is smaller, ranging less than 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) on a side. A microburst usually lasts only 3-5 minutes. Winds will change drastically when a microburst hits a location, then quickly return to the previous direction. The microburst winds can easily reach up to 100 miles per hour but then quickly subside. These strong winds can cause downed power lines or broken trees.

Storm Spotter Training

Since the 1970s, the National Weather Service has operated a storm training program called the SKYWARN Spotter Network. The focus of the program is to help volunteers keep their community safe by accurately reporting severe weather in their local area, especially severe thunderstorm activity. The free training is offered every year by National Weather Service meteorologists. Volunteers learn:

- Thunderstorm development

- Basic storm structure

- Severe thunderstorm components

- NWS storm reporting protocol

- Basic weather safety

Additional information can be found here:

- Cloud Chart

- SKYWARN spotter field guide

- Find a SKYWARN class in your area

- Severe Weather 101

- JetStream Online Weather School

Questions?

Contact the Arizona State Climate Office at [email protected] or visit the Arizona State Climate website azclimate.asu.edu

Authors

- Dr. Randall Cerveny, ASU President's Professor, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning

- Dr. Erinanne Saffell, Arizona State Climatologist, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning (update 2024)

- Juliana Likourinou, Assistant Arizona State Climatologist, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning